Which site would you like to visit?

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.

May 14, 2013

Francesco Falcone’s interview of Produttori del Barbaresco’s Aldo Vacca first appeared in Alessandro Masnaghetti’s Italian wine journal Enogea (Issue No. 43). Translated, from the Italian, by RWC.

In January of 2007, one of the warmest in the Langhe’s history, I interviewed Aldo Vacca, director of the Produttori del Barbaresco. The idea behind the conversation was to learn more about the cooperative and its role in the region. At the end of the day, after an endless series of bottles tasted and a long chat, I discovered much more than one might imagine, information on places, people and production trends tied to the appellation in which Aldo Vacca is a key player, even beyond the cooperative he manages. The account of that day was never published in Enogea, and therefore, it seems fitting to include it in this issue [No. 43] of the journal, as an appendix to the retrospective of 2001 Barbaresco.—Francesco Falcone

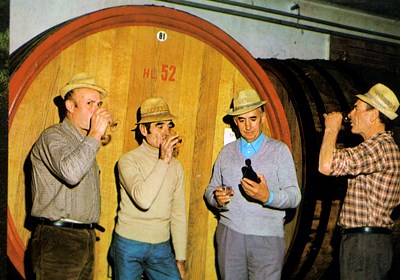

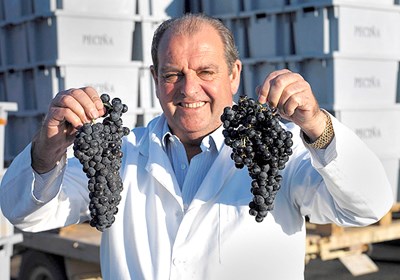

After having spent a good fifteen years of his career at the side of Angelo Gaja, for whom he was a valued assistant, Aldo Vacca, who graduated in 1982 with a degree in agriculture and then earned a master’s, a couple of years later, from UC Davis, since 1998 has been the director of the Produttori del Barbaresco, among the greatest cooperatives in the world of wine. Besides wine, of which he is an expert taster, he has a soft spot for Mozart, for the mountains and for cycling, which, I’d say, he practices often, having seen the excellent physique that belies his nearly 55 years of age. He was destined to helm the cantina, judging by the profound and, I’d say, unbreakable bond that ties his family to the Produttori. His great-grandfather, Giuseppe Vacca, was one of the nine founding members of the first, albeit ill-fated, cantina sociale [community winery] established by Domizio Cavazza—founded March 24, 1898, and shut down in 1925—while his father, Celestino, is considered to be one of the architects of the cantina’s re-founding, together with Don Fiorino Marengo, priest of Barbaresco. The re-founding took place in 1958, the year Aldo was born.

Francesco Falcone

Dear Aldo, I’ll begin right away with a question to try to debunk a cliché. Is Barbaresco still seen as a wine of less importance compared with Barolo or is that just a mantra repeated by critics and by wine drinkers who are are out of touch with reality?

Aldo Vacca

There’s often a basis for clichés, so I won’t be so presumptuous as to think that I can dispel this. However, in essence, a cliché has some truth, either large or small. In this case, I’ll lean towards the latter, at least with respect to the past: Barolo remains the Langhe’s most recognized red wine to the public at large, but Barbaresco, in the last twenty years, has created its own well-defined niche. And I’m hopeful for the future.

Francesco Falcone

You’ll consider what I’m about to ask an elementary question, I’m certain, but your response will probably help readers further understand the genesis of the hierarchy between the two wines [Barolo and Barbaresco]. Tell me, then, what are the reasons that led to the difference—in favor of Barolo—in terms of image and notoriety?

Aldo Vacca

The history is very important, and I believe it bears mentioning because it’s not known by everyone. Barolo was born at the beginning of 1800s, Barbaresco at the end of the same century, basically seventy years later. Barolo boasted rich and powerful figures who had made their first fortunes (Marchesi Falletti, Savoy’s Casa Reale, Camillo Benso Conte di Cavour)—an incredibly valuable dowry for subsequent generations. The “father” of Barbaresco, rather, was a learned man, an intellectual, namely Professor Domizio Cavazza, an Emilian, founder and director of the Scuola Pratica di Viticoltura ed Enologia di Alba [Alba School of Enology and Viticulture], and inspiration behind, and creator of, the first Cantina Sociale di Barbaresco. An extraordinary person, but clearly less influential than the first protagonists of Barolo. Taking this into account, it’s easier to understand why Barbaresco was for many years defined as the “little brother” of Barolo—a definition more linked to history than to presumed vocational differences. One must also remember that the Barolo zone is roughly three times larger than Barbaresco, with more villages, more wineries, more opportunities and synergies of which to take advantage. Our “cousins,” moreover, were very talented at looking out for their prerogatives, including commercial privileges. If you go abroad, in the important distribution channels, it’s easier to find Barolo than Barbaresco. And this is not because Barolo is more “famous” and reliable from a qualitative standpoint, but rather, above all, because it becomes difficult, for us, to find a winery with the capacity to satisfy the demand of the large companies. I’ll give you a practical example: our winery, which I’ve managed for a number of years, is the biggest producer of this wine [Barbaresco], but invariably we have to opt out of participating in the “tender” for Singapore Airlines, which, for its first class, requires a minimum of 40,000 to 60,000 bottles per year, a quantity that we’re not in a position to supply if we don’t want to lose our most faithful clients.

Francesco Falcone

Apparently, Barolo is a more diverse and potentially dispersive appellation compared with Barbaresco, which, on the contrary, is principally a small, homogenous appellation. And yet, in general, the Barbarescos tasted in recent years are far from this theory. My impression is that not everything has been taken advantage of here, particularly from the point of view of viticulture and enology, which they do very well in Barolo. Are you in agreement with this interpretation?

Aldo Vacca

No, I don’t feel at all in agreement with you. In Barbaresco, as in Barolo, there are wines of the highest quality and others of less worth. If there’s an aspect, rather, that should be underlined it’s that our appellation saw a blossoming of new and small wineries only in the last ten years. Therefore, one has to take into account that a good part of the commercial panorama and production is from young, sometimes very young, wineries. When one begins an endeavour rich in variety and in unpredictable complications—like wine—a period, more or less considerable, of experimentation or of settling is natural. I am certain that, in Barbaresco, when less-experienced producers have the chance to mature, they will be able to focus their production with more consistency and personality.

Francesco Falcone

I will be honest, probably too much so, but I assure you that, from the outside, the impression is that the terroir of Barbaresco is less endowed. I am speaking particularly on behalf of many enthusiasts who closely follow the affairs of the Langhe. Do you believe it’s only a question of time, therefore, and not of talent?

Aldo Vacca

I’m sorry that this is the impression that we give as a zone. I was hoping that it was better. I believe that Barolo has a number of leaders who are well known and established, while in Barbaresco, figures like this are more difficult to find, and, therefore, the media impact is much less strong. I do not believe at all, in any case, that the terroir of Barbaresco is less privileged. It is certainly different, but this is a richness, not a limitation. It is this variability, even though the grape variety and appellation are the same, that gives our area the charm that fascinates thousands of drinkers; these differences nourish the concept of terroir. To complete my thought, I’ll tell you honestly that in our zone and in the Barolo zone, there are excellent vineyards and vineyards that are less excellent. Because Barolo is larger, you can count on more areas of good quality. The terroir of Barbaresco, moreover, is also more difficult to read. Here, generally, Nebbiolo has less body compared with Barolo, but it is endowed with the same tannic structure—sometimes even more—and this aspect makes the wines, on average, less balanced in their youth. Rather, if we go and analyze the traditions o n example to follow. In Barbaresco, this role was filled only by the Gaja winery, which nevertheless was, and still remains, a true icon outside of the commune, being so important, unaccessible in certain ways, and, consequently, singular and inimitable.

Francesco Falcone

Visiting the appellation, I had the sensation that Barbaresco has preserved more ties with the past, something which has not happened in the appellation of Barolo, probably also thanks to the historical activity of the Produttori. Is this an incorrect perception?

Aldo Vacca

If by more “connected to the past” you mean more rural, it can be true also for the simple fact that many owners of great vineyards are associated with the Produttori del Barbaresco, and, consequently, they did not have to invest resources in a winery and, generally, in the aesthetic upkeep of their farms. If, rather, by “past” you mean the historical sensibility, I believe that the producers in Barolo have more “awareness of place” and therefore more respect for their own roots. Sometimes I get the impression that for many winemakers in Barbaresco, Barbaresco is not “The Wine,” but only the most expensive red wine in the race. This is a belief that should be reconsidered, in my opinion.

Franesco Falcone

Considering Ariadne’s thread that unites them—namely, Nebbiolo and a shared geological origin of soils—in your view, what are the fundamental differences among the three principal villages of the appellation (Barbaresco, Neive, and Treiso) in terms of “expression of Barbaresco”?

Aldo Vacca

It is difficult to generalize, since the most subtle differences are evident more among the single vineyards than among the three principal villages. Nevertheless, if I must, in the Barbaresco village, one produces Nebbiolo that is elegant, intense, and probably more complete and balanced compared with the other villages. In Neive, the structure tends to dominate the elegance, producing wines that are a bit more robust. This is much more true the more one distances him or herself from the village of Barbaresco. While in Treiso, where the influence of the climate of the Alta Langa is most felt, and where the altitude is higher, on average, they produce much finer wines even though sometimes they are more nervous and less toned down—without forgetting that, here also, the same considerations hold true for Neive in regards to the distance from the village of Barbaresco.

Francesco Falcone

You wrote a book on the great terroirs of Barbaresco, the village, not the appellation. Could you outline your personal hierarchy? Maybe an adjective, an image, a few sentences to describe the character of the best crus of the area?

Aldo Vacca

Also here, to avoid generalizing, I limit myself to the nine crus that we bottle individually at the Produttori, but I do not want to make a classification, which I do not like. I will try to be concise. Essentially, I could tell you that Pora is approachable; Rio Sordo, elegant; Asili, austere; Pajè, bright; Ovello, lively; Moccagatta, floral; Rabajà, complete; Montestefano, powerful; Montefico, austere. Have I been too concise?

Francesco Falcone

Let’s say that you might have held something back. At this point, I have another question that will not be easy for you to answer. As an authority and champion of your appellation, how do you consider the work of Angelo Gaja for your zone? And how do you regard the decision of Gaja not to sell his well-known crus anymore as Barbaresco? Do you have an opinion about it?

Aldo Vacca

The balance between positive and negative aspects, I believe, is certainly in favor of the former, even if only for the notoriety that the appellation gained from the prestige of that brand. Angelo Gaja, still today, never stops promoting his territory all over the world, even if, at times, his decisions brought about less-than-positive results for the image of Barbaresco. His radical choices—Cabernet Sauvignon planted in San Lorenzo, pulling his historic crus outside of the appellation—in fact called the whole system into question. The people assumed that if Gaja renounced such absolute values, he did not believe in the history and values of his own community, even if Gaja himself always denied the alleged loss of faith in the zone. And nonetheless he made the same choices in Barolo, where, by then, he owned more hectares than in Barbaresco. Having said this, today it looks like the environment is calmer, and the period of uncertainty is just a memory.

Francesco Falcone

If you agree, let us part ways by telling each other about a few bottles that we remember with particular joy. I’m talking about Barbaresco and Barolo, I mean.

Aldo Vacca

Off the top of my head, if I think of Barbaresco, our 1978 Rabajà, is still splendid today (if the bottle if well conserved), 1982 Gaja Barbaresco (precise, ample, and lively), and 1971 Rabajà from Cascina Luisin, a lesser-known name, which, in that memorable year, gave the best of itself. For Barolo, though, I say without a doubt Luciano Sandrone’s 1985 Cannubi Boschis, tasted in 1999 (sensational for its ability to blend classicism and modernity) and 1957 Bartolo Mascarello Barolo, from magnum, drunk at home a couple of years ago. It was a bottle that magically framed, in a synthesis of extreme elegance and enviable harmony, the spirit, depth of nuance, and longevity of Nebbiolo from the Langhe.

New discoveries, rare bottles of extraordinary provenance, limited time offers delivered to your inbox weekly. Be the first to know.

Please Wait

Adding to Cart.

...Loading...

By clicking the retail or wholesale site button and/or using rarewineco.com you are choosing to accept our use of cookies to provide you the best possible web experience.